Large chimneys of power plants symbolize pollution and climate change, but also industry and prosperity. Without these clouds of production, we would not have experienced the level of prosperity we enjoy today. In “Power,” I capture this duality of beauty and horror.

The Hemweg 8 coal plant in Amsterdam closed permanently in December 2019

For more than 150 years, coal was the dominant fuel upon which we built much of our prosperity. The smoking chimneys of coal plants, among others, long symbolized wealth and progress. However, in recent decades, they have increasingly become symbols of decline and change—change in our climate and our healthy living environment.

For years, the 125-meter-high chimney and its immense plume of smoke were my beacon in the landscape. The large cloud of steam and waste had a familiar quality. The plume from the chimney showed me that the city was alive and gave me an idea of the wind direction as I cycled in the area.

I often wondered what the inside of such a power plant looked like. When I learned that the plant was going to close permanently, I realized I had to act quickly; otherwise, I would never get the chance to see the inner workings of a coal-fired power plant.

I received permission from the company Vattenfall to follow the workers for a year without restrictions. This allowed me to acquaint my fellow citizens with the people who had provided them with electricity and heat for many years.

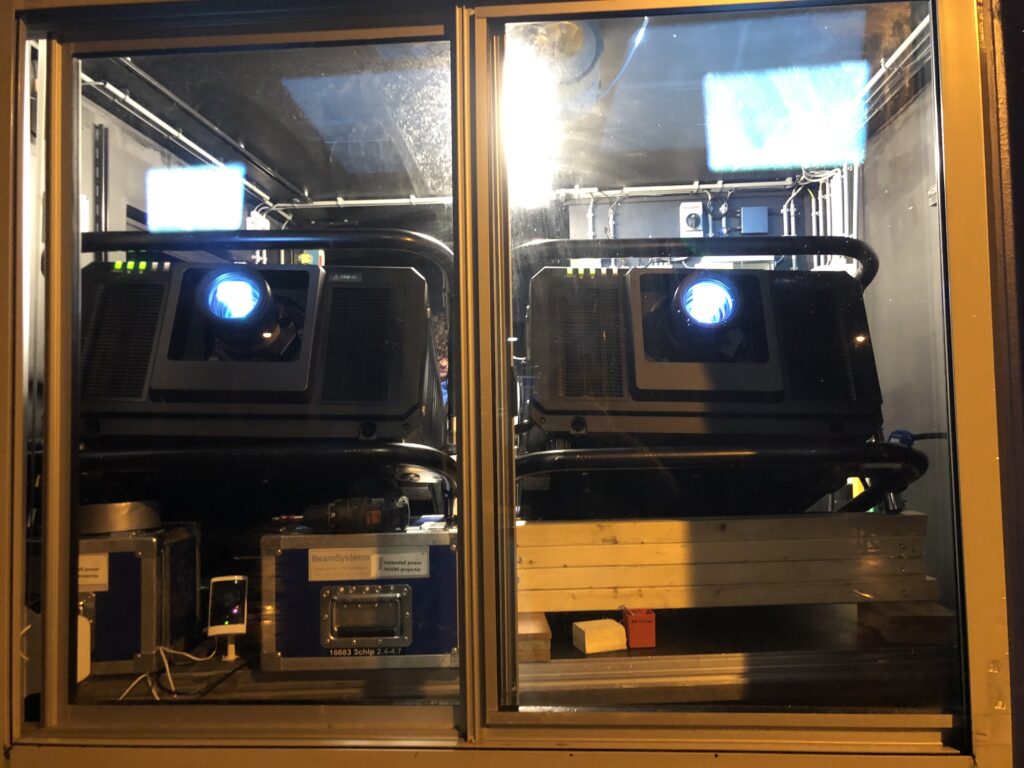

As a tribute to the workers, some of whom had worked at the plant for generations and were now bidding farewell to it, I created a video installation that was projected onto the main turbine house a week before the closure. This 55 by 35-meter projection was visible from afar. The projection featured various teams looking at the camera intensely before walking away. This intense gaze was also meant to make viewers aware of the human effort and technology behind the power outlet that we so casually use to charge our phones every day.

For the projection on the Power station we needed a 30000 lumen beamer. The projection was 55 meter wide and 35 meter high.

The Amsterdam photographer Henk Wildschut (52) is often in search of subjects that at first glance seem to be adequately covered by the media, but on closer inspection turn out to harbor countless surprises. Such as the migrant city that had grown near Calais in France, constructed from waste wood and plastic by the thousands of illegal immigrants who had set their sights on crossing to Great Britain. Wildschut went there for a long time to investigate, and did not find the expected collection of helpless victims, but people who, despite their approached position, wanted to make something of their lives and their stay. This resulted in the prize-winning photo book Ville de Calais.

The accursed Hemweg power plant in Amsterdam-West was also such a large social subject about which another than the often told story can be recorded and captured in photographs. This is what Wildschut has done with designer and picture editor Robin Uleman in the magisterial Hwg, in which the last operational months of the coal plant are chronicled. The book can be seen as a monument to a disappearing industry, as Wildschut calls it, and as a reminder for the two hundred people who worked there.

Hemweg 8, as the coal-fired power plant is called, started in 1994 and was closed, a few years earlier than planned on December 23, 2019, because the Netherlands had to comply with international climate agreements to limit CO2 emissions. Hemweg 8 ran entirely on coal – it was the most polluting power plant in the country, so closure was the obvious course of action. In the autumn of 2018, Wildschut, who like many a resident of Amsterdam had seen the plume of smoke rising from the 175-meter-high chimneys of the power plant for years, wondered: what’s going on inside that enormous colossus, behind that 40-by-55-meter blind wall that every motorist on the Ring Road thoughtlessly drives past?

The photographer raised the issue with the management of owner Vattenfall, who were initially in no hurry to undertake such a photo project – the closure was only planned for six years from now. But when the decision-making process suddenly gained momentum, Vattenfall threw off its shyness and Wildschut landed what he calls his dream assignment. ‘I got a safety course, a helmet and a pass, I could go in whenever I wanted.’ He did so an average of three times a week. ‘The guiding question of my research was: how is electricity made. I wanted to learn about that whole process, from coal to steam – the production inside the gates of the power plant.’

Gradually he got to know the staff, and caught the ‘chatter’ that makes Hwg so attractive. This is how he came across the term ‘monkey hair’, which refers to the formation of algae in the plant’s condensers where the water heated by coal fire is converted into steam. He learned about specimens of the Chinese woolly lobster that is frequently found in the plant’s filters. And he got to know the corporate culture characterized by an unprecedented openness of “men – especially men – digging into the coal with their claws. The type no bullshit, you do your thing.’

When Wildschut suggested that he wanted to take a photo from a position that was impossible to reach, there was always someone who said: wait a minute, we’ll build a scaffold. And it was done within an hour. It’s a mentality that stems from the shipping industry, where many of the technically trained employees have gained experience. On a ship, if something breaks, it has to be fixed. Not in a while, no, right away.’

Slowly, in the book, the secrets of electricity production unfold – from coal conveyor belts and the crushing of the black stone into powder, from furnaces at 1,300 degrees and the gypsum made from the fly ash released from coal combustion. Of acid and salt deposits on the inside of the chimney pipe, clogged feed lines and the men who have to fix malfunctions. A world opens up to you – so much so that you almost regret that politicians ever wanted to close the coal plant.

The people who worked there got a lot of shit thrown at them,’ says Wildschut. After all, they were seen by many as the personification of the climate problem. They would say: ‘The power used by the computer you use to write your articles on climate change comes from us. Of course, the workers could see that burning coal would eventually become untenable. But the human aspect has so often been overlooked in the discussion. It is comparable to the discussion about farmers and nitrogen: there is so much polarization, and too much boorish talk about these people.’

Hwg is intended first and foremost for the staff, almost all of whom were redeployed within Vattenvall after the company ceased operations. At the same time, Wildschut sees the book as a “document of a disappearing industry. Neither the management nor Uleman put any obstacle in his way when taking the photographs. And so the characteristic head of an employee who had worked at Hemweg 8 for decades and who had a serious accident after Wildschut’s photo work at the power station is not missing. The man became an invalid – something that wryly underscores Wildschut’s plea for the human perspective.

Does he think the climate problem will be reduced by the closure of Hemweg 8? Wildschut has his doubts. Of course you have to start somewhere, but the closure was also symbolic. The Hemweg produced 600 megawatts of electricity. The largest power plant in Europe was built in Poland, with a capacity of 5,500 MW.

Concept Book and Design by Robin Uleman

At the end of 2019, the Hemweg Power Plant in Amsterdam was decommissioned. ‘Hw8’ – or HW8, as the plant is known to its staff – is a documentary photo book about this last fully coal-fired power plant in the Netherlands.

The book reveals the hidden world behind the power socket. The closed colossus next to the A10 highway harbors a complex and dangerous environment where everything revolves around the intimate relationship between humans and machines. In the presence of this colossus, with its immense boiler at the heart, encased in a claustrophobic network of pipes, conveyor belts, stairs, walkways, tanks, and turbines, the photographer is a mere speck.

He is allowed to observe for half a year and portrays the extensive machinery and its inhabitants: from the almost otherworldly coal fields to the laboratory; the control room; the workshop and the turbine house; to the 175-meter-high chimney. By the time the book ends in the locker rooms, we have come to know the people who all have something to say about their plant, about the living entity it proves to be with all its quirks and caprices. Even for those who have worked there for half their lives, no day is the same – the plant never fully reveals itself.

This inscrutable, living, and fragmented nature is the starting point for both the design and the edit. The story is constructed as a driving stream of images that begins with the raw coal (C), followed by the power plant as it transforms the coal into electricity, fly ash, gypsum, SO2, NOx, and CO2. ‘Hw8’ seems to fit within this series of chemical formulas as a title. The camera zooms in and out, the images are edited cinematically, and the page numbers at the top emphasize the progress of the process. Regularly, the focus shifts to a specific phenomenon hidden behind a fold-out page, enhancing the feeling of disorientation and the sometimes absurd presence of humans within their own creation.

Short text about the book