In the vicinity of the port of Calais there is an area of a few hundred square meters, known as the ‘jungle’. The inhabitants of this area have travelled many miles to come here and still their journey is not finished. Calais is the starting point for the last and most popular crossing. Thousands have come from Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Eritrea, Somalia, Sudan and Nigeria in search of a better life in England, the destination of their dreams. Not that they are welcome, as illegal immigrants are banned and excluded through a vast system of laws.

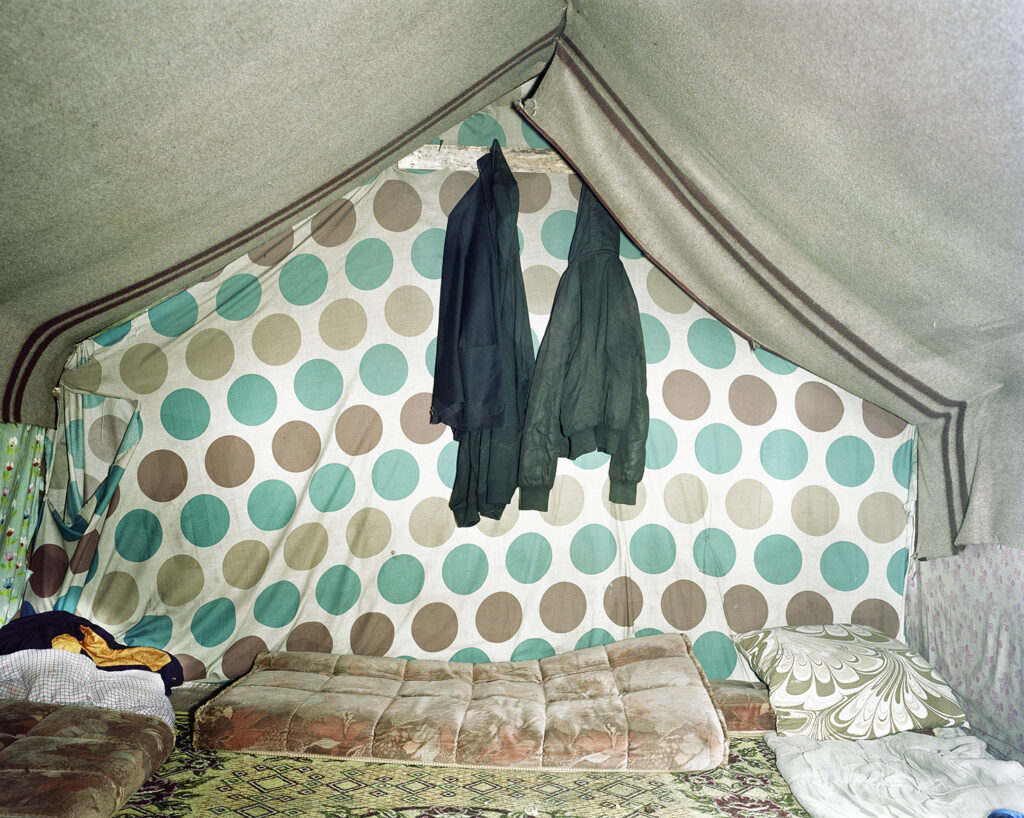

While waiting for the chance to make the long crossing, they build makeshift shelters: tent-like structures of waste materials found in the immediate vicinity of the camp. Even in the best case, it is hard to recognize the cultural character of their country of origin in these structures.

The way in which this basic necessity of life is given shape in the shelters is the ‘leitmotif’ in the documentary photography project that Henk Wildschut started up late 2005 and for which he frequently travelled to Calais, southern Spain, Dunkirk, Malta, Patras and Rome. For Wildschut, the sight of the shelter – anywhere in Europe – became the symbol of misery.

While shelters reveal little or nothing about the wellbeing of their residents, they still become models for the larger, underlying story – one full of violence, fear, desire, courage, sadness and anxiety. In a documentary sense, the shelters cannot pretend to be anything else than what they actually are. This indirect portrayal originates in the moral despair of the photographer: how to depict a humanitarian problem in images without clichés?

The indirect eloquence of the images in Shelter is the connective factor that helps make the receptive viewer feel involved and offers a meaningful alternative to the platitude of photography.

In the vicinity of the port of Calais there is an area of a few hundred square meters, known as the ‘jungle’. The inhabitants of this area have travelled many miles to come here and still their journey is not finished. Calais is the starting point for the last and most popular crossing. Thousands have come from Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Eritrea, Somalia, Sudan and Nigeria in search of a better life in England, the destination of their dreams. Not that they are welcome, as illegal immigrants are banned and excluded through a vast system of laws.

While waiting for the chance to make the long crossing, they build makeshift shelters: tent-like structures of waste materials found in the immediate vicinity of the camp. Even in the best case, it is hard to recognize the cultural character of their country of origin in these structures.

The way in which this basic necessity of life is given shape in the shelters is the ‘leitmotif’ in the documentary photography project that Henk Wildschut started up late 2005 and for which he frequently travelled to Calais, southern Spain, Dunkirk, Malta, Patras and Rome. For Wildschut, the sight of the shelter – anywhere in Europe – became the symbol of misery.

While shelters reveal little or nothing about the wellbeing of their residents, they still become models for the larger, underlying story – one full of violence, fear, desire, courage, sadness and anxiety. In a documentary sense, the shelters cannot pretend to be anything else than what they actually are. This indirect portrayal originates in the moral despair of the photographer: how to depict a humanitarian problem in images without clichés?

The indirect eloquence of the images in Shelter is the connective factor that helps make the receptive viewer feel involved and offers a meaningful alternative to the platitude of photography.

This work was on display in the following exhibitions:

- Galerie Bart: Transit

- The Great Photography Special 2020

- Unseen 2019

- Unseen 2018

19 September 2010 (5 am)

Today I leave for Calais, for the last time. My friend has heard me say this more than once, but this place always pulls me back. “Let’s see what the situation is now.” “It’s an addiction,” she says. In recent years Calais, for me, has become symbolic of the problems surrounding illegal immigration in Europe. It is the place where the hidden world of illegality comes to the surface and becomes visible. Calais is also the place where a better life is dreamed of for the last time. For those who get to the other side, there is only the harsh reality of the illegal life in the big city or deportation back to the homeland.

In 2001 I was in Calais for the first time. Groups of illegal immigrants stormed the Eurotunnel and there was much fuss about the shelter organized by the Red Cross in Sangatte. It supposedly attracted large groups of illegal immigrants trying to come to England through the tunnel. There was then a lot of media attention to this problem. Upon arrival at Sangatte, I was struck by the large number of immigrants and the inevitability of the problem.

At night, I saw groups of men walking around looking for a hole in a fence or an opportunity to climb on a train. What struck me most of all was the ‘dullness’ with which the reporting media came to ‘cover’ their story. It was rumoured that a camera crew was even handing out wire cutters so that the cutting of the fence could be captured on film. I took some pictures at the time, but I decided not to do anything with them.

In 2005 I was asked by Doctors without Borders to make a reportage on earthquake-hit Pakistan. For me, working in a disaster area was a completely unknown thing. I arrived one month after the earthquake and felt – morally speaking – forced to take pictures of the devastation. These are the kind of pictures people want to see of such a disaster. Apart from the misery and sorrow, I saw the resilience of the people and their urge to survive.

What caught the eye most of all was the fact that the tents in the camps had been given a homey touch. So I noticed that people had put up gardens around the entrance of their tent, an image as moving as it is surprising. In one way or another I could, through the need to create order and domesticity, empathise more strongly with their misery. At the same I was painfully aware that this kind of topic wouldn’t work at all back home. Since that time, I am torn between the nature of my personal motivations and the desirability of journalistic convention. Upon my return I examined the possibilities of photographing the phenomenon of domesticity in refugee camps, with the idea to help create an alternative image of refugees in a meaningful way. Shortly afterwards I learned about illegal immigrants in the forests of Calais through the media. The shelter at Sangatte had long been closed; the then Interior Minister, Sarkozy had closed the camp and abandoned its inhabitants at the end of 2002 for populist motives (in his eyes this solved the problem of the illegal immigrants). So this is where I had to go to see what the situation was like.

Beginning January 2006 I left for Calais again, but with a different intention than before. Upon my arrival, I came across groups of men everywhere. There seemed to be more than in 2001. The ones I talked to pointed me to a wooded area just outside Calais. The terrain was sandwiched between a factory and a suburb. From the road there was nothing special to see, just a few villas with backyards bordering the forest. Between the trees I came across colourful shacks made of blankets and clothing and all sorts of waste materials, carefully tied together with bits of rope and tape. It smelled of urine and other waste and layers of clothes and shoes were lying in the mud. I was really surprised; I did not expect seeing something this “un-European” less than 250 km away from my house. A Pakistani boy told me that life is hard in the ‘jungle’ (which is what the place was called). Without basic accommodations of any kind they tried to survive with the support of charitable organizations. Every night they climbed in, on or under a truck, hoping that it would bring them to the Promised Land – Britain – unseen. Some huts were empty because the temporary occupants may have been lucky that night. But there was a bigger chance that they weren’t lucky and were arrested by the police. The empty huts were usually quickly taken by newcomers. So there was this miserable kind of continuity.

The jungle was roughly divided into three areas: the African section, the Indian section and the Pakistani-Afghan section. There was a certain degree of rivalry between these groups that escalated into regular outbursts of violence, often sparked by nocturnal disagreement over which group first succeeded in finding a suitable truck. ‘Finding’ in this context, by the way, really meant that mafia-like gangs offered a truck as a means of transport at a high price.

What touched me most was that the huts were left so neatly, despite the awareness that every day could be the last. Blankets lay neatly folded and coats were tidily hung. For me it soon became clear that these colourful shacks would be “my” symbol for illegality. It allowed me to give a more indirect and subdued picture of what it means to be excluded.

By focusing on something as ‘trivial’ as ‘shelters’ I hope to provoke a more humane compassion in the viewer than by following the standard ‘human interest’ approach in which the so-called ‘story’ of the wretched fellow human is exposed. It’s a bit like how a background reporting relates to hard journalism.

By leaving out information, I appeal to the imagination and empathy of the viewer, with the intention that he or she will create an image of the preservation of universal human dignity in their own mind, set against the oppression of the deplorable housing and living conditions. That dignity is expressed mainly in the neatly folded or hanging clothes, sleeping bags and blankets, the clean-kept surroundings, and the eliminated waste. People remaining human in an inhuman situation.

The camps were regularly cleared by the police but new ones were established just as quickly. In 2009, one camp actually grew into a mega-camp, with a mosque, a bakery and a real camp store. In the heyday of this camp it accommodated more than a thousand Afghans. Late September 2009, the camp was flattened by bulldozers, an event that was accompanied by much media attention. After I had taken pictures in Calais for a whole winter, I looked for other places in Europe where I might find a similar or comparable situation.

My search brought me to Malta, southern Spain, Madrid, Rome, Tenerife and the Greek Patra. During these visits I found the places where the immigrants stayed ‘in transit’ especially interesting. The places where people stayed longer, such as squats, presented to homey an image and, more importantly: I was usually made to feel completely unwelcome. Immigrants in transit have nothing to lose because they have nothing. People who have built a precarious existence have a lot to lose, which is why they don’t want to be noticed.

Being on the move (in transit) leads to temporary solutions to the need for housing – a shelter. Certain creativity is required to build a ‘shelter’ from found materials. Somewhere I recognize those human qualities in these temporary structures; they remind me of camping with the Boy Scouts or building a cabin in the woods, in the attic or under the table. Those shelters gave me safe, secure feelings when I was a child, out there in that big dark attic or in the wet forest. None of this is noncommittal, there is something uncomfortable about this recognition, it creates a false link between my subject and my own life.

The search for shelters occasionally made me face rather difficult decisions. For instance, I was in 2007 in Melilla (Morocco) because I had heard of illegals who camped out in the woods around this Spanish enclave awaiting an opportunity to climb over the fence to Europe. Despite good research I knew within one hour after arrival that for me as a photographer with my specific subject matter there would be nothing here. There were illegal immigrants and big problems, but no huts or temporary shelters. I took some photos with the realization that I probably would do nothing with them- it did not fit in my story.

Try explaining that to people who accost you to tell you their story. They hope that as a photographer I can do something for them. The hope that a journalist can mean something diminishes during the tour of Europe. Shortly after arrival, the men still have great confidence in the press. They want to tell you everything because they are so embittered by all the injustice that has happened and still happens to them.

Their story has to be told to the world and the problems that they face every day could, as far as they are concerned, easily be solved. In a later stage of the journey their cynicism and distrust of the press has grown and after the umpteenth encounter with a journalist who wants to put a story together, there is nothing but distrust and dislike.

During their journey through Europe, they have discovered that the attention by the press for their existence hasn’t done them much good. On the contrary, attention means politicians who want to do something about the situation – and that means “visits” by the police. Attention means trouble. “What is it to us?”, is a common question. “Only you get better by it. We worse. “

After driving for three and half hours I arrive in Calais. Normally you see groups of young men are everywhere. I stop at the place where aid agencies hand out breakfast. Again, nobody. There is a bus from the CRS (Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité), the feared police, from where I am closely observed. I decide to drive past the places where months before I had found many huts. These places had not changed much over the years.

Especially the overgrown bushes in the dunes were always occupied. The dunes are covered with dense thorn bushes. If you didn’t know better, this would seem like a normal piece of nature, but in between the bushes, there are huts hidden. I’ve never been able to make good photo here because of the dense undergrowth.

Again, you immediately notice that the place is deserted. There was always someone on the lookout for the police. Now it’s quiet. When I walk through the bushes, I see garbage everywhere and trampled huts. The camp was obviously abandoned in a hurry. In one camp fire I find a thermos and a notebook with a pen next to it. Everywhere traces of food: cans, discarded empty packs of pasta and rice.

It is clear that the police have been at work here. Life is made impossible for the people here. The camps “visited” by the police a couple times a day. The men are prevented from sleeping and continually chased, until they give up. But these guys do not give up so quickly. They have been in worse predicaments. The chase has been going on for years but the situation there has never changed, let alone improved.

I go back to look at the place where the aid agencies are distributing food. Now I see a couple of Afghan boys. I recognize one of them from my last visit in the spring. He tells me that everyone is gone. To other places where the police leave them alone, like Paris and Dunkirk. The situation in Calais is currently hopeless and it does not make much sense to wait here, the border really seems closed. I wonder how it is possible that the border that has been leaky for years could have suddenly been sealed off so tightly.

According to Frontex (European Agency for the monitoring of the common borders) there are three main reasons: the lack of employment in the EU because of the economic crisis, the stricter immigration and asylum procedures in Member States and effective cooperation with the countries of origin.

There are still a few guys there who arrived a few days ago. Their faces betray a level of disappointment, or rather, defeat which I barely imagine. These guys tell me how their journey through Europe went. The broad outlines of their story are like many stories I have heard before. Most of these guys follow the same route.

Afghans – who in recent years I’ve met the most by far – are left in Turkey by smugglers. With boats they cross the border to Greece. There they are confined in camps and later led into illegality, in many cases with worthless residence papers. But there is currently no work in Greece and survival is almost impossible. The dream must be sought elsewhere. Italy is currently the promised land. To get there, more water must be crossed, from Patra. After that hurdle is taken, disappointment awaits in Italy. Again, they are all but welcome here. Rome is a distribution point. Most Afghans get together at the Roman Ostiense station, for information and to find relative security and safety amongst fellow sufferers.

When you look around you see them at all major stations in Europe. Their destination remains basically still Calais, but there are much less journeys made in that direction now. England was indeed the Promised Land for many years for the illegal worker (here you could work hard undisturbedly and make money for your family), but that seems largely over. The boys who just arrived cannot understand why they cannot go to England. “We just come to work hard. The British were fighting in our country because they supposedly wanted to help us. Now that we come to them because our country is destroyed by war, we are suddenly not welcome. “

The man I met earlier told me that more and more people give up. They give themselves up to the police. The UNHCR has even opened a special repatriation office. This is news to me and makes me sad. Even though it sounds acceptable, the consequences of a return are extremely serious. The loan of a cool € 10,000 to pay the smugglers will never be repaid and brings them and their families in the downward spiral of a bleak and hopeless existence.

After these conversations, I wonder if I should search for new camps around the port of Dunkirk. Who knows, there is still something unexpected going on. But I decide to drive back home. I realize that the rapidly changing political and economic situation in Europe has changed the circumstances of illegal immigrants in a new way, bringing different problems than the ones they have experienced in recent years.

Politicians want to demonstrate that they approach these problems in a decisive manner. The illegal immigrant will now carefully hide from view since being too visible or gathering in groups can lead to immediate action by the police. But as long as there is inequality in the world, the problem will remain, in one form or another. Europe hides more and more behind its barricaded borders, but those who fight for their hopes of a decent life, will always find opportunities to overcome these boundaries.

But those who don’t give up their hopes for their hopes of a decent life, will always find opportunities to cross these boundaries.